Research

Adebola Oshipitan has conducted academic and clinical research on topics like psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for various prestigious institutions like Harvard University to Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He has also written about more personal interests, such as African Hybridization within fashion. His research spans and incorporates multiple disciplines, including medicine, fashion, social psychology, music, anthropology, and more. His current research focuses on Negrophilia's global implications in shaping how Black popular culture is consumed and loved compared to how Black people are perceived and treated within different global communities between Western and Eastern societies.

Featured Research

MY SOCIOCULTURAL PERSPECTIVE

MY PROJECT PROPOSAL

The Gatekeeping of Psychedelics

Harvard University-Nock Lab

The Current Issue

💡

Western psychiatry has revived the clinical interest in psychedelic research in treating psychological disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and addiction in the 21st century (George et. al). Despite new medical knowledge being gained on psychedelics’ healing potential, Western medicine continues to frame psychedelic science’s origin from a Eurocentric viewpoint that begins with 20th century researchers, disregarding the major contributions of indigenous people in influencing modern day practices. Modern psychedelic medicine and science owes its success to the traditions and ritualistic practices of indigenous peoples’ plant-based medicines. Despite their millennia-spanning work, indigenous and Black communities have been restricted from accessing the healing practices they founded and developed. These groups have been exposed to more stress and mental illness as disenfranchised people compared to white populations, but participant groups in psychedelic studies are mostly comprised of white people. Systemic discrimination and racism, such as the War on Drugs, violent over-policing, racist policies, drug stigmatization (against psychedelic healing practices), etc. has led to a lack of minority group inclusion in psychedelic medicine. Psychedelic-related studies require improved minority representation in their patient populations, so clinical efficacy not only reflects white populations but Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) as well.

CALLS TO ACTION

- Fund BIPOC psychedelics researchers

- Tenure and provide positions to BIPOC psychedelics researchers

- Minimum quota for minorities in research

- Provide visibility, safety, and support for individuals who have been doing psychedelics work in the shadows

- Establish community partnerships with indigenous peoples for psychedelic research

- Legalization of psychedelics

- Lower financial barriers for receiving psychedelic care through government lobbying and enacting new public policy

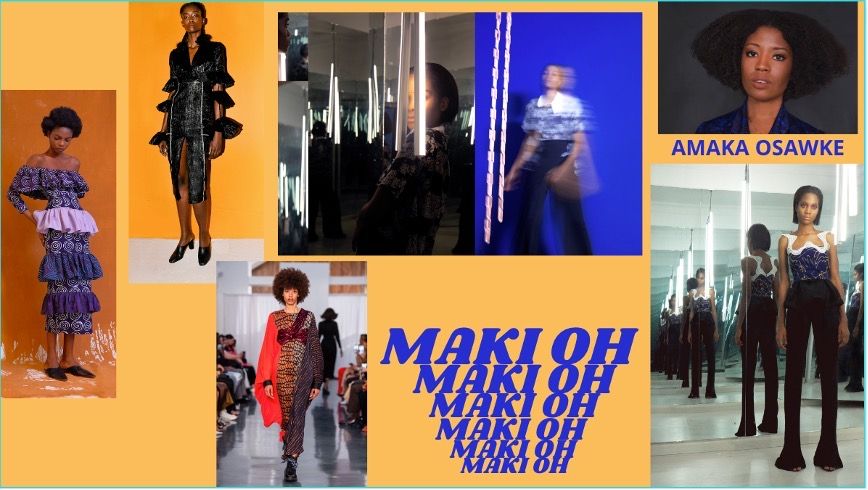

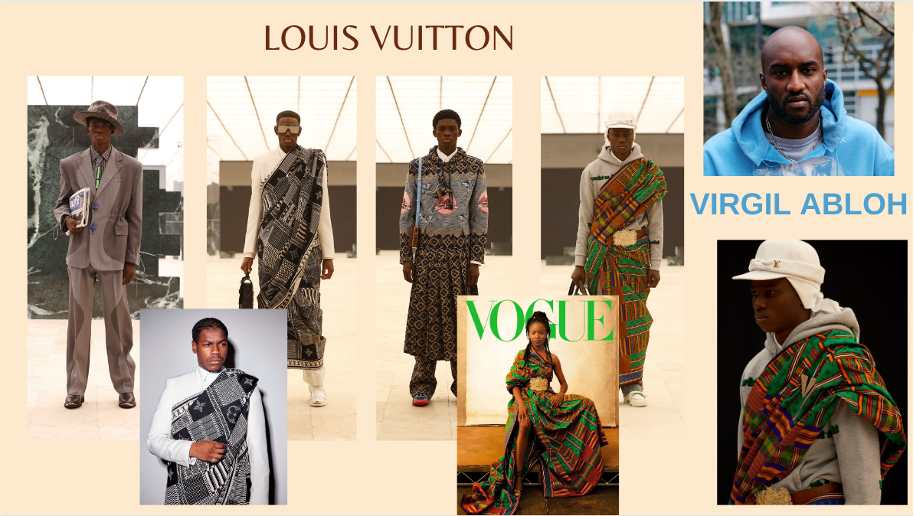

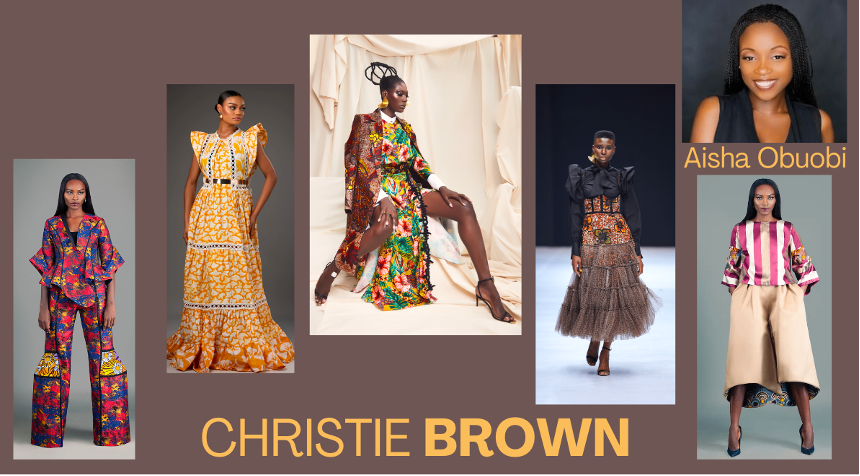

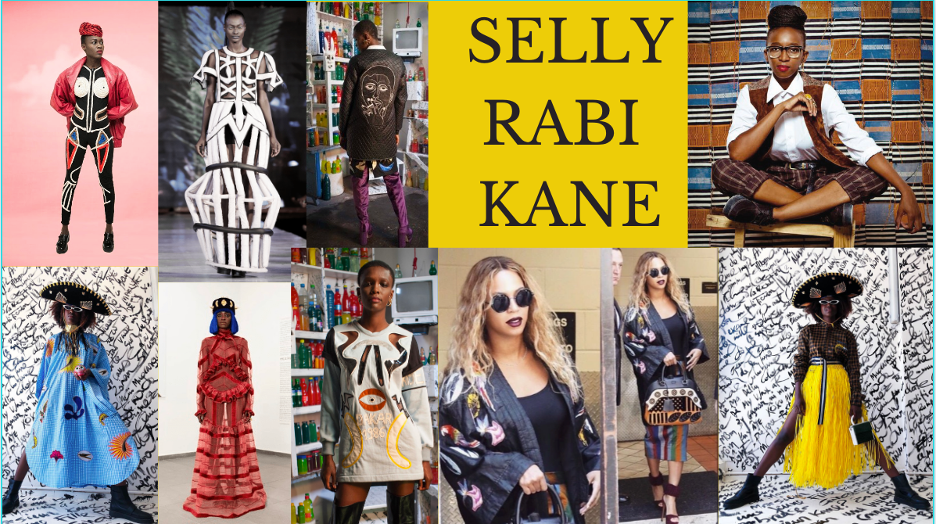

African Hybridization

How European Colonization Shaped Modern African Fashion

What is African Hybridization?

💡

As a result of European colonization, formerly colonized African tribes and groups have adopted aspects of Western traditions and artworks and integrated signs and symbols into their existing traditional clothing, garments, style, and textiles, birthing the fashionscape of African Hybridization. Eurocentric structures and customs were gradually imposed on and normalized in African colonies. Thus, fashion in the European context becomes the new standard in African communities and civilization. The ““language” of fashion presents itself as European almost everywhere and constantly reiterates its anchor in the European-urban world” (Mentges, 2011). As a result, to be recognized and legitimized in the Western fashion scape (that encapsulates most of the world), African countries and communities adopted European values and norms. Additionally, the effects of diaspora, migration, and exile along with enforced foreign value systems on a population are irreversible and permanently alter a group’s relationship and understanding of their tradition. Post-colonized peoples have realized that despite their best efforts to reclaim their original pre-colonial identity based on their ancestor’s traditions, they cannot. They have opted to create new cultural meanings and traditions, reconciling past heritage and modern-day colonial influence to shape a hybrid future. This future takes various forms that “may be contingent to [European] modernity, discontinuous or in contention with it, resistant to oppressive, assimilationist technologies” (Bhabha 1994, 6), but all African countries, ethnic groups, and individuals consult past and ongoing colonial cultural exchanges and attempt to answer the vital question “where do we as a culture go from here?”

THE ANSWER